Printing note: This design was created to be 8.5″ x 14″ and the design pdf will print best on legal size paper.

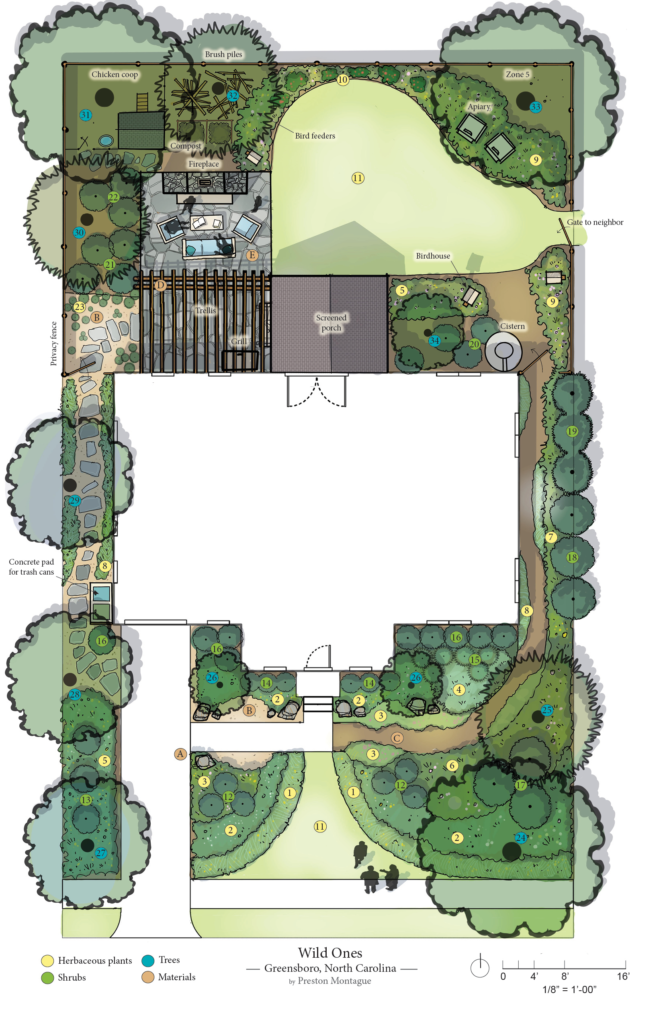

Wild Ones Meet the Designer Webinar

Greensboro Native Garden Design Discussion with Designer Preston Montague

Artist’s Statement

Landscape design connects us to our environment, to each other, and to ourselves. Because our environment impacts our physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being, as well as that of other species, I frame landscape design as an act of healthcare.

Overview

The mild climate of the Piedmont affords gardeners an opportunity to stretch their zone and indulge in a cosmopolitan plant palette. To the hilly west, gardeners can exploit slopes and cool microclimates to lure mountain plants and traditional English garden fare into the suburbs. To the east, gardeners can play with palms and tropical-looking plants that persist through winter, a season that feels less like a period of dormancy and more like a fitful nap.

Although there is economic value in creating landscapes that cater to our aesthetic fancies or nostalgia, the urgent work for the Piedmont’s landscapes at the start of the 21st century is to respond to the one-two punch of rapid development and climate change. Landscapes that reduce heat load, reduce light and noise pollution, collect stormwater, feature keystone native plant species, and hyper-concentrate resources for wildlife will become increasingly important if the area is to retain its renowned livability and natural beauty. The responsibility of this work falls not only into the hands of municipalities, developers, and design professionals but also into the hands of home gardeners whose landscapes impact the health of the environment more than they may realize.

Most of us are not living in as natural a condition as we might hope, and gardeners and landscape pros can frustrate themselves trying to use planting design to reanimate some mythical, virginal past. Our work now is not to recreate what was, but rather to invent new ecologies that respond to the specific pressures of our time. We may find success by triangulating indigenous practices with new technology, with boosting ecosystem service using new arrangements of naturally occurring plants, and by resisting the melancholy pleasures of climate guilt and deciding instead to have some fun!

Site Analysis at a Glance

Begin your landscape design journey by creating a map of the wild energies that influence your landscape. Document sun and shade patterns, stormwater flow and pooling, prevailing wind direction and areas of stagnant airflow, as well as shallow and steep slopes. Also, document how areas of your landscape make you feel. Photograph your property in different seasons and at different hours to capture patterns you may not have noticed. Recognize how these wild energies interact to create distinct microclimates. Document these microclimates and let them guide your decision-making about what activities to place in them.

Take hikes in conservation areas and document the plants, animals, water bodies, and overall character of ecosystems you identify as healthy. How can you model the soils, hydrology, and plant life in these areas on your property? Native isn’t only about plant provenance. Native is also about how plants organize themselves within a system, as well as the climate that surrounds them. Consider the difference in plant organization between a typical East Coast forest and a West Coast forest, and how the climate factors of both impact that organization.

Planning and Installation Tips

- If possible, study your space for a year before designing the landscape.

- Design by subtraction first. Remove invasive species, refuse chemicals unless necessary, reduce light and noise pollution, and remove high-maintenance plantings and materials.

- Conserve and protect what patches of habitat remain. Connect these patches with vegetation corridors. When patches get too stable, cut into them to create edges to reactivate biodiversity.

- Design for the activity. As you’re planning an outdoor space, consider first the activity, how much room it requires, and what shape, and what surfaces, plantings, and furniture support the activity.

- Identify projects in your landscape plan that will have the most impact and tackle those first.

- Saturate time and resources into the most important landscape spaces, then guide the remaining landscape into a stable, low-maintenance condition. Typically for me, that’s planting a forest anywhere outside of my primary activity zones.

- Avoid using lawn as a default condition. Lawn is best when it’s used deliberately, as it is the highest-maintenance vegetation you can choose. Lawn may be simple, but it’s not easy.

- Houses, hardscapes, and lawns are concentrated bundles of energy that impact the local climate. Not only do they influence the behavior of air flow, but they also impact the water cycle through heat storage and reflected light.

- February’s wet cold, and August’s marathon drought, will likely be the biggest factors determining the success of your planting choices.

- Design during the hottest part of summer, mobilize your contractors and assemble your materials at the edge of summer and fall, then focus work on the landscape between Halloween and Memorial Day.

- Trees and shrubs do well planted between Halloween and Valentine’s Day, forbs and graminoids do well planted between Valentine’s Day and Memorial Day. If you have to plant both at one time your best bet is February.

Helpful Hints

- Focus on preserving and planting keystone species. These are species that have superlative resources for other species. Oak trees are an example.

- Target specific species of animals and insects you want to serve in the landscape and plant for them (ex. plant Rudbeckia sp. for goldfinches).

- Provide perennial, multi-seasonal food sources (nectar, fruit, and seed) through both woody and herbaceous plants so that wildlife have a stable source of nutrition.

- Leave a space (aka Permaculture Zone 5) where habitat can evolve without your intervention. For example, leave areas of the landscape alone where native bees can build homes underground without the danger of being mulched over.

- Avoid or reduce mulch use by incrementally adding new groundcover plants with seed and plugs. Leave some room in the budget every year to plant more groundcover until there’s no more ground left to cover.

- Don’t feel compelled to use the existing soil on your property and don’t assume it is a natural condition. It may be subsoil that was never meant to see the light of day in your lifetime but was exposed when developers stripped the topsoil layers off. You can bring in 50/50 topsoil/compost mixes for new beds or bury the landscape in layers of cardboard and wood chips and allow that to become soil over time.

- Disturbing existing soil can wake up a latent seed bank that creates more work for you in the long run.

Plant Communities and Materials

Herbaceous

Plant graminoids in drifts, herbaceous plants in blocks. Choose one species in each plant group to focus on, rather than an even mix of species. Plant in odd numbers, and plant larger drifts and blocks of small species, and smaller drifts and blocks for larger species. The following correspond to the landscape plan provided and are meant to be followed like a recipe:

- Structural Edge: 60% short graminoids like Carex cherokeensis and C. pensylvanica, Juncus tenuis, and Sporobolus heterolepis, and 40% forbs like Aquilegia canadensis, Coreopsis lanceolata, Asclepias tuberosa, and Achillea millefolium. Plant everything 18” apart. You can also seed these forbs in winter to get an extra dense planting. Plant bed can be mown occasionally to keep plants more compact.

- Low and Flowery: 40% medium graminoids like Carex vulpinoidea, Juncus effusus, Schizachyrium scoparium, Andropogon ternarius, and 60% forbs like Liatris spicata, Pycnanthemum tenuifolium, Rudbeckia fulgida, Echinacea pallida, Bidens aristosa, and Eryngium yuccifolium. Plant everything 24” apart. Substitute forbs with Aquilegia canadensis, Chasmanthium latifolium, Monarda fistulosa, Eupatorium perfoliatum, and Eurybia divaricata if planting in the shade.

- Sunny Corners and Edges: Gaillardia pulchella, Phlox paniculata, Bouteloua gracilis, Helenium autumnale, Coreopsis verticillata, Juncus tenuis, Zephyranthes atamasco, Stokesia laevis. Plant everything 18” apart, except for phlox, which needs more room between one another.

- Rain Garden: 40% graminoids like Rhynchospora colorata, Carex cherokeensis and C. muskingumensis, Juncus effusus, and 60% forbs like Monarda punctata, Verbena hastata, Asclepias incarnata, Lobelia cardinalis, Zephyranthes atamasco, Iris virginica, and Packera aurea.

- Buffers and Screening: 60% large graminoids like Panicum virgatum and Sorghastrum nutans and 40% medium forbs like Rudbeckia fulgida, Symphyotrichum novae-angliae, Rudbeckia maxima, Helianthus angustifolius, Vernonia noveboracensis, Pycnanthemum muticum, and Eutrochium purpureum. Plant everything 48” apart. Seed Aquilegia canadensis, Rudbeckia hirta, and Achillea millefolium as a weed control barrier beneath the larger plants.

- Complicated Shade Patterns: 60% graminoids like Carex cherokeensis and C. vulpinoidea, Juncus effusus and J. tenuis, and Chasmanthium latifolium, and 40% forbs like Monarda fistulosa, Eurybia divaricata, Aquilegia canadensis, Achillea millefolium, Polystichum acrostichoides, Eupatorium perfoliatum, and Packera aurea. Plant everything 30” apart.

- Weed Control for Under Trees and Shrubs: 60% graminoids like Carex vulpinoidea and Sporobolus heterolepis, and 40% Rudbeckia fulgida, Symphyotrichum novae-angliae, and Pycnanthemum muticum. Plant everything 36” apart.

- Path Edge (facing east): 60% graminoids like Carex cherokeensis or C. pensylvanica, Chasmanthium latifolium, Polystichum acrostichoides, Heuchera americana and H. villosa, Tiarella cordifolia, Iris cristata, and Eurybia divaricata. Plant everything 18” apart.

Path Edge (facing west): 40% graminoids like Carex cherokeensis, Juncus tenuis, Zephyranthes atamasco, Aquilegia canadensis, Achillea millefolium, Hypericum prolificum, and Coreopsis verticillata. Plant everything 18” apart. - Cut Flower Bed: 40% graminoids like Carex vulpinoidea, Juncus effusus, Schizachyrium scoparium, Muhlenbergia capillaris, Sporobolus heterolepis, and 60% forbs like Rudbeckia fulgida, Achillea millefolium, Phlox paniculata, Monarda fistulosa, Echinacea purpurea, Helianthus angustifolius, Hibiscus coccineus, Symphyotrichum novae-angliae and S. oblongifolium, Eryngium yuccifolium, and Coreopsis lanceolata. Plant everything 36” apart and seed Aquilegia canadensis and Achillea millefolium in as weed control.

- Veggie Garden Companions: Carex cherokeensis and Juncus tenuis, Aquilegia canadensis, Achillea millefolium, Monarda fistulosa, Verbena hastata, Coreopsis lanceolata, Stokesia laevis planted 18” apart from each other.

- Lawn: Zoysia sod or fescue and white clover from seed.

Woody Plants

Plant woody plants singly in small beds, or in larger quantities using odd numbers as bed size increases. Plant woody plants in triangle formations and don’t be too careful about spacing them evenly.

- Symphoricarpos orbiculatus can be used to add winter interest and bird resources to add complexity and persistent structure (albeit floppy) to large herbaceous plantings.

- Ilex decidua makes a good translucent screen where having some visibility is important, particularly around driveways and in parking lots.

- Hypericum densiflorum and Yucca filamentosa make good, low foundation plants, especially against south and west faces of a building.

- Clethra alnifolia makes an excellent focal point plant for rain gardens and other areas where moisture is abundant for at least six months per year.

- Vaccinium virgatum makes a lovely shrub against the house where it can be more easily defended from birds competing with you for fruit. Vaccinium also has interest in all four seasons and can be hedged if a little more formality is desired.

- Viburnum nudum and Viburnum dentatum make good, all-purpose screening shrubs and can tolerate complicated shade patterns beneath trees.

- Alnus serrulata makes an excellent fast-growing screen in wet to moderate conditions and is good along property edges because it does not produce fruit or seed that will be a concern for neighbors.

- Ilex glabra makes an excellent fast-growing evergreen screen in wet to moderate conditions.

- Hydrangea quercifolia can be sensitive to sun and drought and enjoys the protection of structures that provide relief from afternoon sun.

- Hydrangea arborescens is a nice addition to patio areas and as an accent to evergreen screening plantings.

- Aesculus sylvatica is a shade tolerant and highly ornamental shrub. Note that seeds are poisonous, so best to avoid them if dogs or young children may ingest them.

- Herbs and edible plants do very well planted into grit and gravel areas, and can be accompanied by Carex eburnea or Carex bicknellii.

- Acer rubrum is a classic, fast-growing street tree for sun or part-sun with outstanding fall color and little mess, which is ideal near walking areas.

- Ilex opaca makes a great screening tree and evergreen focal point in both sun and shade. Excellent plant for bird nesting as well.

- Cercis canadensis is the perfect small tree for under power lines, or as accent trees in the front of the house.

- Asimina triloba is an excellent small tree that bears fruit that is fun to share with the neighborhood.

- Magnolia virginiana is a striking focal point plant and a good, casual screening evergreen tree, and is particularly useful in wet areas.

- Betula nigra is a very fast-growing, keystone species that is good for growing fast in shade, but does drop a lot of limbs and has thick surface roots that make it a bad candidate for lawn or patio areas, but fine for side yards and buffers.

- Nyssa sylvatica is a striking tree with unusual structure and outrageous fall color. Can occasionally bear tremendous amounts of fruit.

- Quercus species are critical keystone species and excellent for the backyard, as a street tree, or in a buffer. Toggle both white and red oak species for variety.

- Cornus florida is the state flower of North Carolina and has tremendous, four-season character, as well as superlative resources for wildlife. A favorite for birds to nest in.

- Liriodendron tulipifera makes a very fast-growing screen or shade tree and can be a great candidate for a treehouse.

- Chionanthus virginicus is an outstanding small tree around the house and can tolerate deeper shade than many understory trees.

Materials

Select materials that are available within 300 miles if possible.

- Granite or limestone boulders create microclimates in the landscape.

- Decomposed granite as a mulch can create a dry microclimate and superior drainage for plants that naturally occur on slopes, rocky outcrops, or sandy environments. Does have some limitations as a pathway material, so provide granite, limestone, or slate steppingstones.

- Wood chips make an excellent mulch when allowed to compost for a year. Regular applications of wood chips help prevent weeds from occurring in paths.

- Trellises, pergolas, arbors, and posts can be made from cedar or black locust for natural longevity.

- Granite and slate stones make for a warm hardscape surface in the winter and can be regularly or irregularly shaped.

Musings on Management

- Most of your problems in the landscape are likely due to not having enough plants.

- Close the loop: maximize resources already on site (ex. compost for soil conditioning and leaf litter as mulch)

- Weeding will be necessary in new plant beds, but after three or four years you can minimize it by incrementally adding more and more groundcover plants every year until your plantings are so dense and biodiverse that weeds learn to comingle gracefully or are pushed out entirely. Some stubborn woody weeds will always make their way into the system from bird activity, but that can be more easily remedied in the typical residential garden bed than Bermuda grass or nut sedge infestations.

- Make decisions about the landscape based on your capacity to manage what you create. If all you have time to manage is a few planters on the patio, then perhaps you should consider building the patio and just reforesting the rest of your property.

- Planting types from highest to lowest maintenance: lawn, annual beds, forb-heavy planting, graminoid-heavy planting, shrubs, trees.

- Leave the leaves and don’t be too tidy. Resist the urge to do major landscape clean-ups except for a spring cleaning session after it’s warmed up for a week or two. The leaf litter, hollow stems, and other nooks and crannies between plants are all places insects hide during winter. Native is also a process.

- During spring clean-up, keep stems, branches, logs, and other organic material on-site to decompose and provide habitat for insects, aka baby bird food. Lay the trimmed material down around the plants to decompose and nourish the soil. Alternatively, identify tucked-away areas where you can spread organic material, create brush piles or build a wattle fence.

- Avoid pesticides of any kind in the landscape. This includes mosquito and other pest control services that apply broad spectrum, persistent pesticides that will kill all beneficial insects and pollinators. Remember that plants are meant to be eaten and that a little bit of leaf damage means your landscape is part of the ecosystem. Look at holes in leaves as an achievement.

- Burning the landscape, if you’re able, is a powerful tool for creating flushes of biodiversity. Be careful to create refuges of unburned areas each year so as not to incinerate all insect life in the leaf litter. Burn on a ⅓ area per year rotation cycle.

- Learn the top invasives for your area and prioritize their removal.

- Relax your grip on the landscape and practice allowing natural processes to happen here and there. Allow the plants to mess your design up a little bit and surprise you. The result may be greater biodiversity and a more beautiful setting than you planned!

PLANT LIST

American Alumroot(Heuchera americana)

American Holly(Ilex opaca)

Aromatic Aster(Symphyotrichum oblongifolium)

Arrowwood Viburnum(Viburnum dentatum)

Atamasca Lily(Zephyranthes atamasca)

Bicknell's Sedge(Carex bicknellii)

Black Gum(Nyssa sylvatica)

Black-Eyed Susan(Rudbeckia hirta)

Blanket Flower(Gaillardia aristata)

Blue Grama(Bouteloua gracilis)

Blue Vervain(Verbena hastata)

Blunt Mountain Mint(Pycnanthemum muticum)

Boneset(Eupatorium perfoliatum)

Butterfly Weed(Asclepias tuberosa)

Cardinal Flower(Lobelia cardinalis)

Cherokee sedge(Carex cherokeensis)

Christmas Fern(Polystichum acrostichoides)

Coralberry(Symphoricarpos orbiculatus)

Crested Iris(Iris cristata)

Dense Blazing Star(Liatris spicata)

Eastern Beebalm(Monarda fistulosa)

Eastern Redbud(Cercis canadensis)

Flowering Dogwood(Cornus florida)

Foam Flower(Tiarella cordifolia)

Fox Sedge(Carex vulpinoidea)

Garden Flower(Phlox paniculata)

Golden Ragwort(Packera aurea)

Hairy Alumroot(Heuchera villosa)

Indian Grass(Sorghastrum nutans)

Inkberry(Ilex glabra)

Ivory Sedge(Carex eburnea)

Lanceleaf Coreopsis(Coreopsis lanceolata)

Large Coneflower(Rudbeckia maxima)

Little Bluestem Grass(Schizachyrium scoparium)

Muhly Grass(Muhlenbergia capillaris)

Narrow-Leaved Mountain Mint(Pycnanthemum tenuifolium)

Narrowleaf Whitetop Sedge(Rhynchospora colorata)

New England Aster(Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

New York Ironweed(Vernonia noveboracensis)

Northern Sea Oats(Chasmanthium latifolium)

Oak species(Quercus spp.)

Oakleaf Hydrangea(Hydrangea quercifolia)

Orange Coneflower(Rudbeckia fulgida)

Painted Buckeye(Aesculus sylvatica)

Pale Purple Coneflower(Echinacea pallida)

Palm Sedge(Carex muskingumensis)

Path Rush(Juncus Tenuis)

Pawpaw(Asimina triloba)

Pennsylvania Sedge(Carex pensylvanica)

Possumhaw(Ilex decidua)

Prairie Dropseed(Sporobolus heterolepis)

Purple Coneflower(Echinacea purpurea)

Rattlesnake Master(Eryngium yuccifolium)

Red Maple(Acer rubrum)

River Birch(Betula nigra)

Scarlet Rosemallow(Hibiscus coccineus)

Shrubby St. John's Wort(Hypericum prolificum)

Smooth Hydrangea(Hydrangea arborescens)

Sneezeweed(Helenium autumnale)

Soft Rush(Juncus effus)

Southern Blue Flag Iris(Iris virginica)

Split Bluestem(Andropogon ternarius)

Spotted Beebalm(Monarda punctata)

Stoke's Aster(Stokesia laevis)

Swamp Milkweed(Asclepias incarnata)

Swamp Sunflower(Helianthus angustifolius)

Sweet Joe Pye Weed(Eutrochium purpureum)

Sweetbay Magnolia(Magnolia virginiana)

Switchgrass(Panicum virgatum)

Tag Alder(Alnus serrulata)

Threadleaf Coreopsis(Coreopsis verticillata)

Tickseed Sunflower(Bidens aristosa)

Tulip Poplar(Liriodendron tulipifera)

White Fringe Tree(Chionanthus virginicus)

White Wood Aster(Eurybia divaricata)

Wild Columbine(Aquilegia canadensis)

Yarrow(Achillea millefolium)

ABOUT THE DESIGNER

Preston Montague is a landscape architect and artist who developed a passion for the natural world while growing up in the rural foothills of Virginia. Currently, he lives in the Piedmont of North Carolina working on projects that encourage stronger relationships between people and their environment.

DESIGNER STATEMENT

Landscape design connects us to our environment, to each other, and to ourselves. Because our environment impacts our physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being, as well as that of other species, landscape design is an act of healthcare.

Growing the Native Plant Movement Together

July 22nd at 5:00 PM (CDT)

The closing event of this year’s Less Lawn More Life Challenge, will be led by Lisa Olsen, Chapter Liaison at Wild Ones. In this webinar, you’ll learn how small, personal actions like planting native species and removing invasives, can ripple outward to inspire neighbors, change policies, and reshape communities.

About Wild Ones

Wild Ones (a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization) is a knowledgeable, hands-on, and supportive community focused on native plants and the ecosystem that depends on them. We provide resources and online learning opportunities with respected experts like Wild Ones Honorary Directors Doug Tallamy, Neil Diboll, and Larry Weaner, publishing an award-winning journal, and awarding Lorrie Otto Seeds for Education Program grants to engage youth in caring for native gardens.

Wild Ones depends on membership dues, donations and gifts from individuals like you to carry out our mission of connecting people and native plants for a healthy planet.

Looking for more native gardening inspiration? Take a peek at what our members are growing!