Printing note: This design was created to be 8.5″ x 14″ and the design pdf will print best on legal size paper.

Wild Ones Meet the Designers Webinar

Princeton Discussion with Designers Lisa McDonald Hanes & Julie Snell

Designer’s Statement

The Mid-Atlantic Region, Princeton, NJ, specifically, was inhabited before the American Revolutionary War. Land development patterns and housing types show this age coupled with modern demands for density and ways of living that meet a wide range of population needs from university students to young families to the elderly. For this reason, our example housing templates look different than the other cities and regions represented in the Wild Ones native garden designs. The designers recognized that an example of native garden design must offer ideas that can be applied to all the ways we are living in our region today.

The designers encourage those using these two garden templates to understand their place within the ecoregion. The potential complexity of gardening can sometimes feel overwhelming. Even we are sometimes hindered by this. But let’s not be! All gardening is experimentation and a handshake with the natural world where there are no guarantees. Just begin; start trying and learning. Not everything works out, so go easy on yourself.

The pandemic revealed the importance of healthy outdoor spaces close to where and how we live. Our design practice focuses on making positive places for people while building resilient landscapes for today’s climate impacts and ecosystem health. If you only have access to a small outdoor space, you can still be a native plant gardener. If you have access to a large parcel of land, you can contribute to the health and well-being of the larger community. Creating a native plant garden will provide food and habitat for native insects and birds, improve stormwater management, clean the air, and overall provide beauty and joy. The majority of land in the United States is in private hands. Begin doing your part in Wild Ones Honorary Director Doug Tallamy’s Homegrown National Park one step at a time.

Soil

Start with a soil test. The Princeton area spans the transition from the Inner Atlantic Coastal Plain – with soils of gravels, sands, and silts – to the Ridge and Valley ecoregion, where soils tend to be stony, shallow, acidic, and not very fertile. Valley soils are derived from sedimentary stone and glacial till tends to be well-drained, deeper, and fertile. This may be the parent material for your soil, but you may find urban fill or cycles of disturbance in built-up areas.

Climate

Our humid, hot summers are getting warmer and our winters less cold. If you are on a ridge, perhaps you have more air flow than if you are in a valley where humidity or lack of wind may affect your garden with powdery mildew. Our significant annual rainfall is growing, though we experienced drought conditions in the summer of 2022. This was followed by the soaking rains following two hurricanes/tropical storms. Plan around the feast or famine cycles by understanding your place within your watershed. If you are on a ridge, perhaps you have free-draining soils that shed water versus in a valley where water will collect. Consider ways to manage stormwater; you may need to direct it, slow it down, allow it to sink in or store it.

Anthropogenic Influences

The age or density of development in your area may significantly impact the quality of landscape areas. Cycles of disturbance in developed areas often cause the loss of top layers of soil, low organic matter, causing high rates of compaction. Extensive paved areas of roads and parking lots impede stormwater infiltration and increase the velocity and volume of stormwater being directed to the sewer systems. Building materials, concrete, brick, stone, and black asphalt roofs hold heat and increase the urban heat island effect keeping ambient temperature elevated even during nighttime hours. These are all reasons to improve the ecological function of your landscape to lessen the impacts of development.

Understanding the Drawings

Plan and elevation are different types of drawings used by landscape architects to graphically represent a design. A plan drawing is a drawing showing a view from above. A site plan is a common design drawing for graphic representation of a layout, showing relationships between structural and landscape elements to scale. They are not drawn in perspective and there is no foreshortening. An elevation drawing shows a vertical depiction looking straight at a space from a particular line within a site, as if you were directly in front of a building and looked straight at it. Elevation drawings are orthographic projections. Elevations are not drawn in perspective, and there is no foreshortening.

Methodology

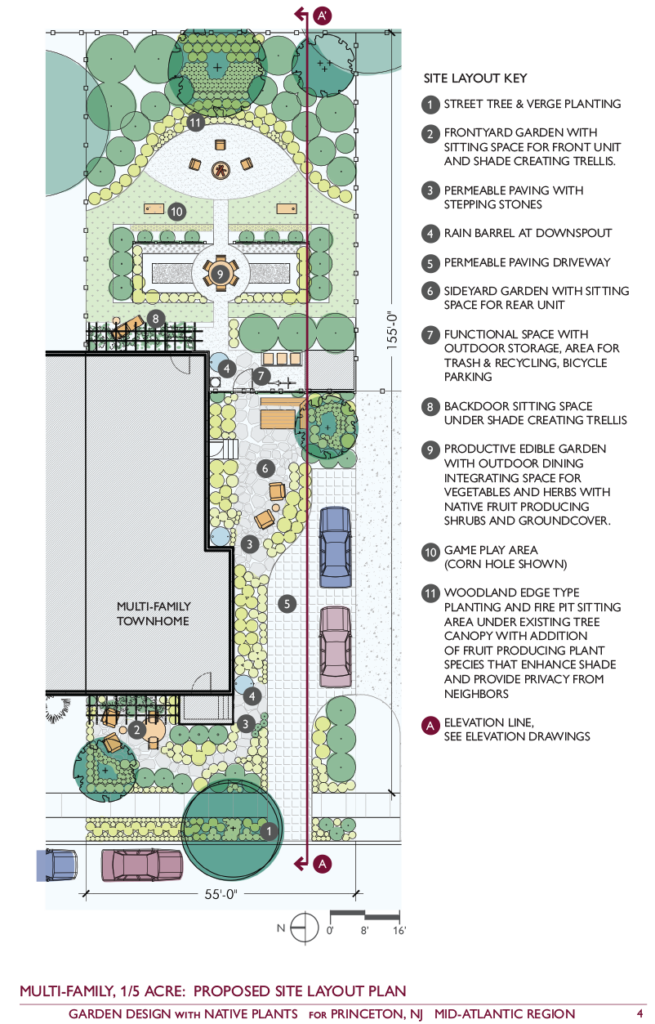

The Multi-Family Template offers ideas that can be applied to just a postage-stamp front area with a stoop or to a broader townhome yard with or without parking on the property. The front is a full sun exposure, close to the public right of way, and blends curb appeal with a semi-private seating area for the front unit. The side yard allows access to both units and rear yard, a private sitting space for the rear unit, stormwater capture, vehicle and bicycle parking, and mundane items like outdoor storage and waste collection. The rear yard spans from full sun closer to the home to shade under neighbors’ trees in the back. Various ways to use and play in the yard are accommodated, from relaxing by the back door to eating in the productive garden, playing games, or sitting by the fire pit.

To begin the design process, the designers started with a site inventory and analysis. All climate factors were evaluated, from the more sunny and hot front space to the cooler, shadier back area. The amount of pavement was noted, along with the lack of stormwater capture and outdoor space for the residents to use in a meaningful way. The landscape offered very little biodiversity, and the few plants other than turf grass were invasive plant species.

The design uses as little as possible paved surfaces and returns the landscape to a healthy plant palette that serves the human inhabitants and the full ecosystem. Water capture is encouraged by transitioning away from paved, compacted or turf grass surfaces. Rain barrels are installed at the roof downspouts for use with gardening or holding runoff until after peak rain events. Plant selection was driven by fitting the right plant to the sun/shade exposure and the highest yield in ecosystem function. The design can be achieved in a D.I.Y. manner and modest budget in a short period or phased in over time.

Where to begin – remove any harm, such as invasive plant species, pruning damaged limbs, or removing dead plants. From there, pick some easily achievable, low-hanging fruit with big impact to get a win and start gaining gardening experience. Always take on only as much in a phase that you can successfully implement and maintain until the plant establishment period is complete. This may be only one year for perennials and grasses but can be two years or more for woody plants. For instance, one would not want to decide to plant the entire backyard in a year where you may not be able to keep up with watering and weeding. In the early phases, start with moves that build long-term bones, including planting trees and improving healthy soils. Many people believe the garden year starts in the spring, but it would be wise to shift your mentality to beginning in the fall. Planting in early fall allows some root establishment before winter dormancy sets in and by the time the heat of next summer comes around, the plants will be a little more resilient. A focus on fall for planting will be easier on you and the plants.

Optional Phasing

Year One

- Remove invasive plants.

- Move the shed from the N.E. rear yard to the transition between front and back yards and install the rain barrels and trellises at the doorways to offer shade on windows and an easily plantable, fast-growing upgrade.

- ‘Lasagne Gardening’ or sheet mulching is a minimal-effort way to remove turf grass while working with natural cycles and building soil. Begin removing lawn grass in the verge, front garden, and rear garden area that backs to neighbors where the screening shrubs and trees will surround the fire pit and directly under the back door trellis. Place sheets of cardboard and add a topping 4″ -5″ layer of woodchips (typically available for free from a local arborist company); this will block light and smother the grass.

- Continue regular mowing for areas that will remain as lawn, but plan to mow according to grass height vs. a weekly or bi-weekly schedule. Set mower blades to 3.5″ and let the grass grow to 3.5″ or 4″, keeping the clippings at less than a third of the length and letting clippings remain on the lawn. The clippings will decompose easily and return nutrients to the soil at that length. A longer grass blade will provide more shade to the soil and discourage the germination of weed seeds. Eliminating the grass under the trees will reduce resource competition between tree roots and grass.

- After two months of smothering grass, start planting, beginning with the trees in the verge, front and rear yards, then filling in the front yard, back door garden and fire pit gardens. Shredded bark mulch can be used as a temporary surface treatment in sitting areas until more permanent permeable paving can be installed.

- Cover any exposed soil around young plants with shredded leaves, bark mulch, or ‘green mulch.’ – groundcover plants that quickly cover bare soil—reducing water and weeding needs around immature plants. The green mulch may live under maturing plants for some time and then die back as other taller plants mature, shading out the groundcover (see plant list notes).

- In the fall, sow any plants desired from seed for next year’s planting in a container that may be left outdoors for natural seed stratification. Burlap or wire mesh covering may be necessary over seed trays to protect them from squirrels or other scavengers. Consider this step each fall.

Year Two

- Remove pavement at the side yard gardens against the length of the house and for the sitting area by the rear unit.

- Test the soil after pavement removal for fertility and compaction rates. Decompact as necessary, begin rebuilding the soil health and structure with amendments such as organic matter in the form of compost and biochar.

- Add stepping stones or permeable paving for access to doorways and under the sitting areas in the front and side yards. The area around the garden shed and entrance to the rear yard can be completed at this time as well.

- Plant the side yard gardens.

Year Three

- Begin killing/removing lawn grass in the remainder of the rear yard.

- Add stepping stones or permeable paving to frame out the productive garden and build the berry trellis.

- Plant the productive garden and lawn replacement where foot traffic is needed for circulation or play.

Year Four

- Complete the driveway transition from impermeable asphalt to permeable pavers.

- Reassess all garden areas, monitoring where success is occurring or where infill of plants species that are thriving would be beneficial.

Resources

Invasive Species

Invasive Plants

- Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health

- Mid-Atlantic Exotic Pest Plant Council Plant List

- P.A. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

Research

PLANT LIST

The list includes plants for a sun to part-sun, free draining site without pressure from herbivores such as deer and rabbits. Plants edible for people are included.

American Cranberry Bush(Viburnum trilobum)

American Wisteria(Wisteria frutescens)

Anise Hyssop(Agastache foeniculum)

Anisescented Goldenrod(Solidago odora)

Appalachian Blazing Star(Liatris microcephala)

Bearberry(Arctostaphylos uva-ursi)

Black-Eyed Susan(Rudbeckia hirta)

Blackberry(Rubus canadensis)

Blackhaw Viburnum(Viburnum prunifolium)

Blue Vervain(Verbena hastata)

Bottlebrush Buckeye(Aesculus parviflora)

Bush Honeysuckle(Diervilla lonicera)

Bushy Bluestem(Andropogon glomeratus)

Butterfly Weed(Asclepias tuberosa)

Carolina Jessamine(Gelsemium sempervirens)

Chokecherry(Prunus virginiana)

Cinnamon Fern(Osmunda cinnamomea)

Clustered Mountain Mint(Pycnanthemum muticum)

Common Blue Violet(Viola sororia)

Common Elderberry(Sambucus nigra canadensis)

Common Milkweed(Asclepias syriaca)

Coral Honeysuckle(Lonicera sempervirens)

Creeping Phlox(Phlox subulata)

Cup Plant(Silphium perfoliatum)

Eastern Blue Star(Amsonia tabernaemontana)

False Sunflower(Heliopsis helianthoides)

Fire Pink(Silene virginica)

Golden Alexanders(Zizia aurea)

Golden Groundsel(Packera aurea)

Gray-Headed Coneflower(Ratibida pinnata)

Green-Headed Coneflower(Rudbeckia laciniata)

Hairy Alumroot(Heuchera villosa)

Hawthorn(Crataegus viridis)

Highbush Blueberry(Vaccinium corymbosum)

Hubricht's Bluestar(Amsonia hubrichtii)

Indian Grass(Sorghastrum nutans)

Indigo Bush(Dalea pulchra)

Lady Fern(Athyrium filix-femina)

Lanceleaf Tickseed(Coreopsis lanceolata)

Letterman's Ironweed(Vernonia lettermannii)

Little Bluestem Grass(Schizachyrium scoparium)

Lyreleaf Sage(Carex socialis)

New Jersey Tea(Ceanothus americanus)

Northern Blazing Star(Liatris scariosa)

Partridge Pea(Chamaecrista fasciculata)

Path Rush(Juncus Tenuis)

Pawpaw(Asimina triloba)

Plantain Pussytoes(Antennaria plantaginifolia)

Prairie Goldenrod(Solidago nemoralis)

Purple Milkweed(Asclepias purpurascens)

Raspberry(Rubus Idaeus)

Red Chokeberry(Aronia arbutifolia)

Red Osier Dogwood(Cornus sericea)

Robin's Plantain(Erigeron pulchellus)

Royal Fern(Osmunda regalis)

Self-Heal(Prunella vulgaris)

Shrubby St. John's Wort(Hypericum prolificum)

Sideoats Grama(Bouteloua curtipendula)

Smooth Aster(Symphyotrichum laeve)

Social Sedge(Carex socialis)

Spicebush(Lindera benzoin)

Sundrops(Oenothera fruticosa)

Sweet Fern(Comptonia peregrina)

Tufted Hair Grass(Deschampsia cespitosa)

Virginia Strawberry(Fragaria virginiana)

White Beardtongue(Penstemon digitalis)

Whorled Tickseed(Coreopsis verticillata)

Wild Columbine(Aquilegia canadensis)

Wild Stonecrop(Sedum ternatum)

Wild Sweet William(Phlox maculata)

Willow Oak(Quercus phellos)

About the Designers

Lisa McDonald Hanes is a registered Landscape Architect, co-owner/operator of Redbud Native Plant Nursery and a founding principal of TEND landscape architects. With a land ethic formed from her family’s farming heritage and more than twenty years of professional work with landscapes, Lisa’s focus is fostering connections between people and their environments and improving quality of life by altering how we perceive, use and care for landscapes. Educated at Purdue University, with a Bachelor’s of Science in Landscape Architecture, Lisa has worked directly with community groups, municipal agencies, a wide range of design professionals and private homeowners in cultivating landscapes like our health depends on it.

Julie Snell is a founding partner of TEND landscape architects and co-owner/operator of Redbud Native Plant Nursery in Media, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia. Julie has a background in Fine Arts, a Master’s Degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania and is a certified arborist. For more than twenty years, Julie has worked in both the public and private realms, focusing on the bridge between design and landscape management. As founder and co-chair of the Landscape Management Forum, she has forged a partnership with landscape managers throughout the Philadelphia region. Julie has been an adjunct instructor at Temple University in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Horticulture. She is currently serving on the Board of Trustees for the Ecological Landscape Alliance.

Free National Webinar: From Wasteland to Wonder with Basil Camu

February 18th at 6:00 PM (CT)

Our upcoming webinar with Basil Camu explores practical, evidence based ways to heal suburban and urban landscapes by working with trees, soil, and natural systems, drawing on real world practices from Leaf & Limb and community centered models for restoring life where we live, work, and play.!

About Wild Ones

Wild Ones (a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization) is a knowledgeable, hands-on, and supportive community focused on native plants and the ecosystem that depends on them. We provide resources and online learning opportunities with respected experts like Wild Ones Honorary Directors Doug Tallamy, Neil Diboll, and Larry Weaner, publishing an award-winning journal, and awarding Lorrie Otto Seeds for Education Program grants to engage youth in caring for native gardens.

Wild Ones depends on membership dues, donations and gifts from individuals like you to carry out our mission of connecting people and native plants for a healthy planet.

Looking for more native gardening inspiration? Take a peek at what our members are growing!