Designer Statement

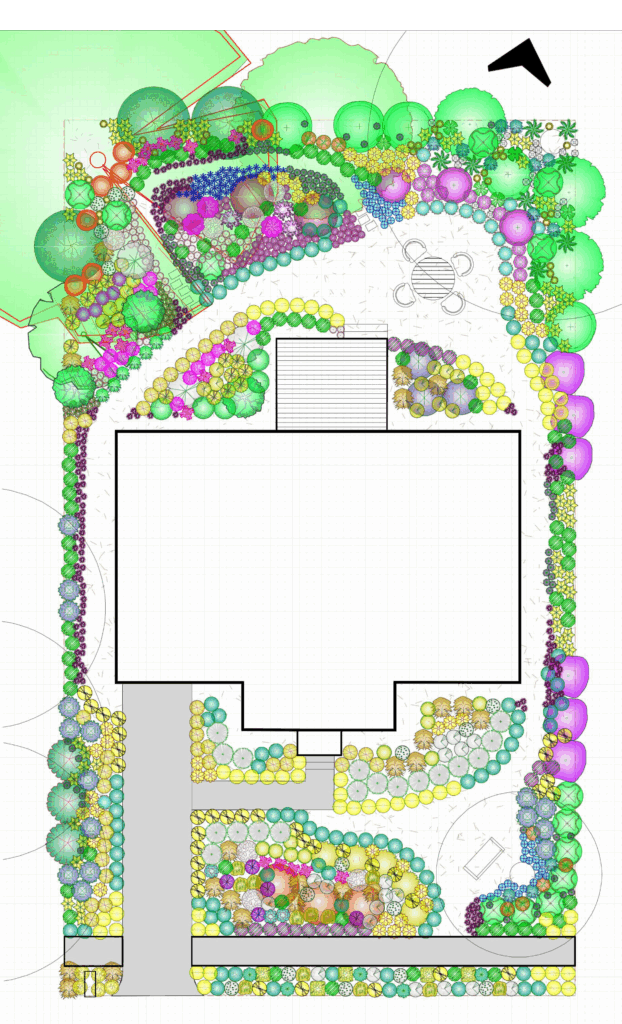

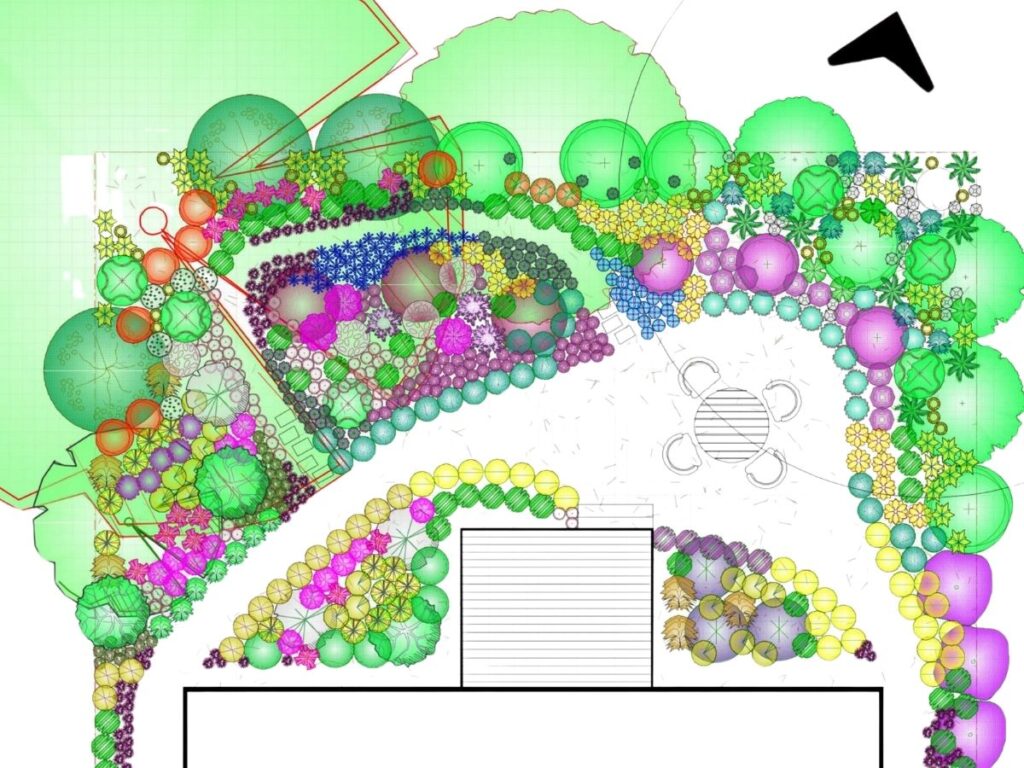

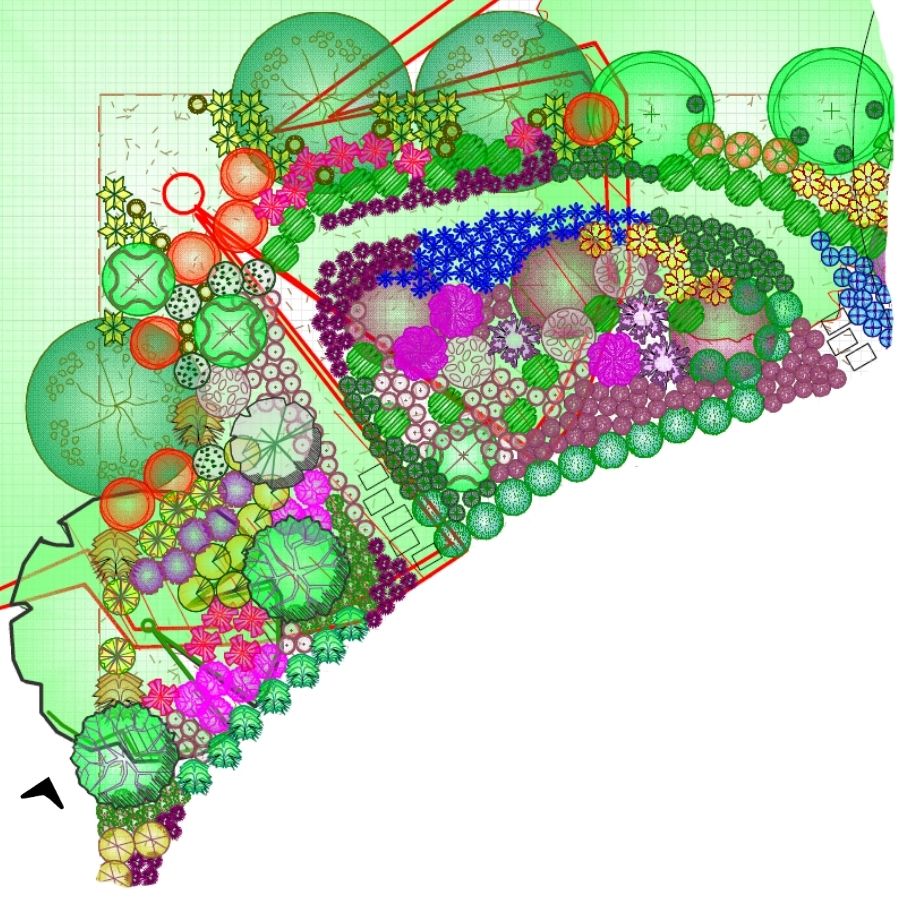

In this sample design, I have offered specifications for all the areas of the landscape around the house. I find it useful to work from a broad, anchoring vision. A full landscape design lends a sense of coherence, gives you a big picture view, and can help you keep your plantings legible and coherent. In execution, it often works best to use the design as a reference, deciding which part of the project you wish to start with, taking it in phases, and adjusting elements of the design as you go to suit the needs of your site, your budget, and your preferences.

Each part of your landscape can mesh with other parts if you plant in stages and plant purposefully. A great way to start is with small, big-impact projects like establishing trees and shrubs or by removing some lawn to put in a small pollinator meadow. These kinds of projects will give you a starting point from which you can continue.

To emphasize the importance of maintaining urban canopy, the sample design incorporates several existing trees and develops a coordinated set of plantings that will fit a variety of site conditions, including conditions that will change over time.

For the best support of wildlife, I believe we should plant as many keystone species as we can, and to the extent feasible, plant for all of the seasons. Consider planting your property as a “woodland edge.” This type of planting is important for wildlife as it provides food and shelter for many species. Birds rely heavily on a dense shrub layer for food and shelter. Layering your landscape is aesthetically appealing, but it is critical for supporting wildlife.

I like to plant smaller plants but more of them. Perennials especially grow really fast and a small perennial or grass even in plug size can be full-sized in one season. The more plants you get in the less weeding and maintenance you can expect over time. You can strike a balance with planting density and budget by sticking to smaller plants.

Ultimately, these choices are influenced by both budget constraints and site conditions. It also is helpful to remember that, in time, plants will find where they want to be.

I’d also like to add a note on lawns and lawn alternatives. For this design, I have chosen to plant native plants throughout the landscape. Turf may be necessary because of HOA rules or for recreation. The important thing to consider is the intent of the space. Can we plant enough native plants, refrain from fertilizers and other chemicals on the remaining play turf, and foster a space that is supporting wildlife? I think the answer is yes.

I hope this design inspires you to create gardens that work for wildlife and humans alike.

Pete Corbino, District Native Plants

Overview

The region surrounding Virginia’s capital is a beautiful and ecologically important part of the Commonwealth that also lies at the crossroads of two major geographic and ecological divisions. Richmond sits at the Fall Line between the Piedmont and the Coastal Plain, which marks an ecological transition zone between central and eastern Virginia. Following European colonization, much of the land was heavily farmed, and much of the native forest and savanna were lost. More recently, as agriculture has moved west, the area has seen an increase in successional forest. Planting regionally native plants is a great way to support wildlife and help buffer the Chesapeake Bay in an area that continues to see human population growth.

In this design, I have chosen appropriate companion plants that rely on a combination of Coastal and Piedmont species. It is prudent to consider which plants will better tolerate extremes. Virginia is known for hot and humid summers, but as our world grows hotter, it makes sense to consider native species that can withstand increasing temperatures and potential droughts.

The changing climate makes it even more important to support wildlife and find ways to be more self-sufficient. I like to incorporate edible and medicinal plants into designs for landscapes that also provide wildlife benefits. Many native plants have been used for food and medicine, some for millennia. Some plants included in this design are elderberry, chokeberry, huckleberry, strawberry, and Vaccinium spp.

Site Conditions

This sample design has been developed for a site with a general southern exposure and some existing native trees common in the Richmond area. Existing trees are useful when planning for a site because they offer hints toward the plant communities that will work well in that location.

A row of Pinus taeda (Loblolly pine) trees in the neighbor’s property on the west side suggests the site is located on a remnant of pine flatwood. The back yard also has several oak trees (Quercus spp.). Oaks are a common canopy tree over much of the Greater Richmond area.

The front yard boasts a specimen of the state tree, Benthamidia florida (flowering dogwood, previously called Cornus florida). Flowering dogwood is both a classic landscaping tree and a dominant native understory tree found in many plant communities in the region.

Given the pre-existing trees, the design considers the sun conditions around the trees together with the overall southern exposure when thinking of companion plants and what the soil and moisture conditions will be like under and around the trees.

Getting Started: Prep Work

Prepping a site for new plants is usually straightforward as long as the soil doesn’t need decompaction. Even if you will not do the installation yourself, it is wise for homeowners to note the sun, soil, and moisture characteristics throughout the space. This knowledge will help you understand the plant selections in this sample design and adjust them as needed to best fit the conditions of your site. It also is important to carefully remove any invasive plants and non-native vegetation you choose not to retain.

Some Practicalities

For long-term success, consider some important things before you begin work:

- Contact Virginia 811. Call or file online (https://va811.com/) at least three days before any digging project. Utility lines will be marked free of charge; lines must be clearly re-marked if weeks or months pass before digging begins. If you hire a contractor, they are required to contact 811, but as the landowner, you must confirm lines are marked before work starts.

- Private utility lines. Virginia 811 does not mark privately installed lines such as water/sewer connections to the house, lines to detached structures, invisible fences, satellite or dish cables, propane tanks, or private wells. Factor these in when planning.

- Herbivores. Expect deer and rabbits to browse. Protect young plants with liquid deterrents or fencing until they are established.

- Chemicals. Stop all chemical applications. Avoid spraying for mosquitoes and do not apply herbicides, fungicides, insecticides, or synthetic fertilizers. These harm pollinators, wildlife, and soil health. If neighbors spray, you may need to have a frank conversation about how it impacts your shared ecosystem.

Lawn Removal

Lawns shed rainwater quickly, sending runoff into streets and storm drains. Native plantings, with deep roots, absorb rainfall and protect water quality. Reducing lawn area supports wildlife and helps protect the Chesapeake Bay from nutrient and chemical runoff.

This sample design eliminates lawn entirely, but if you wish to retain a small play or gathering area, consider sustainable groundcovers or sedges instead of turf. Lawn removal can also be phased to keep projects manageable.

Common methods include manual sod cutting removes turf and is an effective method that reduces grass regrowth and solarization or smothering. Whatever method you choose, the goal is the same: replace monoculture turf with diverse native plantings.

Working With This Design

- Get inspiration. Observe your existing site and nearby landscapes. Central Virginia’s transition between Piedmont and Coastal Plain offers diverse plant options. Use the sample design as a guide but adapt to your site.

- Assess sun, soil, and water. Track shade patterns, drainage, soil type, pH, and moisture. Consider soil tests or amendments if your site was disturbed by development.

- Inventory existing plants. Keep mature native canopy trees whenever possible. Remove invasive plants, and consider replacing exotic shrubs with natives. Resources like Plant RVA Natives and the Virginia Native Plant Society provide helpful references.

- Expect evolution. As canopy trees grow, light conditions shift. Meadows trend toward grasses over time. Native gardens are dynamic; you can hold the design steady with care, or allow natural succession to shape it. Always remove invasives.

Embrace Plant Communities

Assemble groups of companion plants that reflect natural communities and thrive in your site conditions. Plant densely and favor smaller sizes for easier installation, quicker establishment, and lower cost. Aim for 75–90% cover at maturity to minimize weeds and erosion.

In Central Virginia, both Piedmont and Coastal Plain species are appropriate. This design includes species from both ecoregions.

Value Straight Species, Value the Canopy

Favor straight species (true native forms) to preserve genetic diversity and maximize wildlife benefit. Maintain or plant canopy trees whenever possible—urban canopy reduces heat islands, improves air quality, and supports equity by cooling neighborhoods.

If space is limited or utilities interfere, use understory trees. Remember that newly planted trees won’t provide shade for years; plant companions for sun initially and adapt the landscape as shade increases.

Key Features

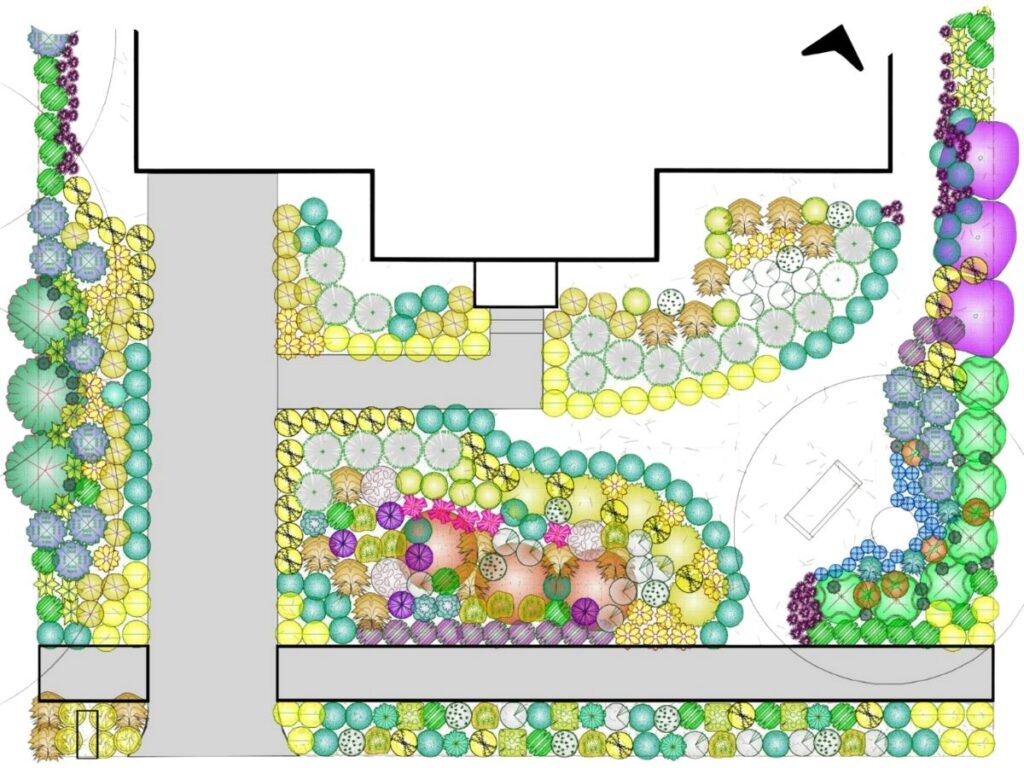

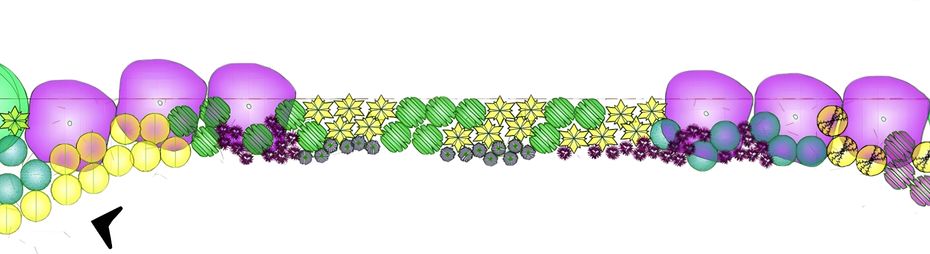

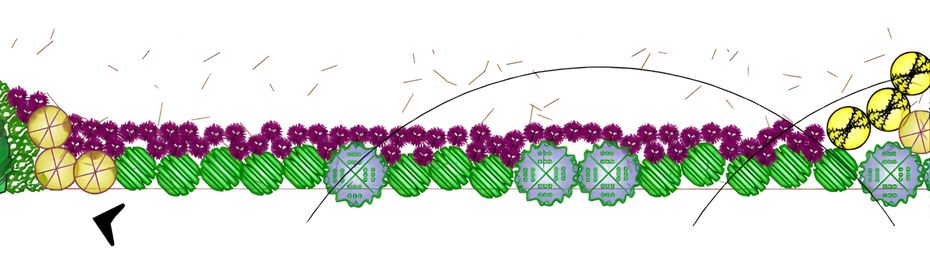

Front Yard

A small meadow-like area is planned for the sunniest spot in front of the house, and this theme continues into the hellstrip. When planting in spaces like this it is useful to include species that bloom throughout the season and to be aware that, over time, grass species tend to dominate. In meadow plantings it’s advisable to plant at least 20% grass species, whose inflorescences add beauty and benefit wildlife. If you wish to keep more wildflowers in the mix, occasional dividing or replanting will help, but it is also fine to let the beds evolve naturally.

Some of the species highlighted in this area are:

- Shrubs:

- Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius): A larger shrub with fragrant spring blooms and a dense habit that supports wildlife.

- New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americanus): A compact shrub that continues the meadow theme with fragrant spring blooms..

- Grasses:

- Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium): A smaller grass that works well along edges.

- Wild rye (Elymus virginicus): A cool-season grass that complements earlier-blooming wildflowers and tolerates some shade.

- Purple love grass (Eragrostis spectabilis): A smaller grass effective along edges.

- Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans): A graceful, clumping grass that adds height and texture.

- Wildflowers: This mixture of plants ensures that something is always blooming, providing pollen and nectar.

Early Season Blooms

- Foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis)

- Lance-leaved coreopsis (Coreopsis lanceolata)

- Butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa)

Midseason Blooms

- Spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata)

- Slender mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium)

- Whorled coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata)

- Boneset (Eupatorium sessilifolium)

- Dense blazing star (Liatris spicata)

Late Season Blooms

- Orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida)

- Spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata)

- Slender mountain mint (Pycnanthemum tenuifolium)

- Whorled coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata)

- Boneset (Eupatorium sessilifolium)

- Dense blazing star (Liatris spicata)

Mailbox Area and Plantings by the Front Entrance

The full-sun meadow theme continues by the mailbox. I encourage homeowners to feel free to use tall plants and grasses if you desire to build up the structure around the mailbox. Heliopsis helianthoides (false sunflower) is a sunflower relative that tends to bloom after Coreopsis and before the other sunflowers, and can be used anywhere there is full sun. I use it in meadow plantings frequently.

Also continuing the full-sun plantings, the beds to the east and west of the walkway that leads to the front door include a hedge of New Jersey tea (Ceanothus americana), which gives some structure and a hint of formality to the gardens. However, these beds emphasize shorter wildflowers and grasses so as not to obscure the front of the house. An additional species used in this space is gray goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis). It is a common shorter goldenrod, it can be used in spaces where shorter plants are desired or even on an edge or border.

Front Garden, West Side

The garden to the west of the driveway is designed for part-shade conditions because of the existing pine trees, and features plants that are typically a component of pine flatwoods or acidic oak intermediary forests. Areas under pines will have some shelter from the sun but won’t have as much seasonal shade as areas under deciduous trees. Shrubs and forbs selected for this area include:

- Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia): Common evergreen heath shrubs found throughout Virginia.

- Black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata): An important blueberry relative producing small edible fruit; clonal and generally more available than other native blueberries.

- Common violet (Viola sororia): An underutilized wildflower that will grow in pretty much any condition and readily spreads, often serving as a living green mulch without impeding other natives.

- Woodland sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus): A tall, shade-tolerant sunflower. This plant can get tall, so I have placed it with the Kalmias. When adapting this design, note that areas under pines wouldn’t have as much seasonal shade as areas under deciduous trees.

Front Garden, East Side

The plan for the east side of the front garden makes use of the existing dogwood tree (Benthamidia florida). Here are shade-tolerant wildflowers and a few sedges, as well as a back line of maple-leaf viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), a smaller, flowering viburnum common throughout Virginia that produces berries, which are great winter food for birds. Additional species to highlight include:

- Lyreleaf sage (Salvia lyrata): Planted along the edge for its shade tolerance.

- Woodland phlox (Phlox divaricata): A shade-loving spring bloomer that offers fragrant blue flowers.

- Eastern red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis): A spring-blooming perennial that provides early color and nectar for pollinators.

- Blue wood sedge (Carex flaccosperma): A medium-sized clumping sedge that enjoys dry shade. Its blue-green leaves pair well with other shade-tolerant plants in this spot.

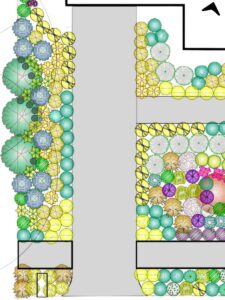

Pathways

Before moving back into other areas of the design, it’s worth taking a moment to consider pathways. This design includes hardscaped paths (e.g., the front walkway and sidewalk by the hellstrip) softer surfaces, and pathways (e.g., the seating areas under the Dogwood tree and off the deck, and the softer pathways alongside the foundations of the house and deck) and an access path leading into the deep shade garden under the largest trees. Some considerations for pathways include:

- Hardscaped surfaces typically include impervious surfaces, which will affect drainage (and can help dictate which plants will work best in those areas.

- Softer surfaces, like wood chips, leave your options open and give a natural aesthetic to the landscape. Wood chip paths also can make good buffer spots between properties or landscape features.

- Oak, locust, and hickory chips will break down slowly, whereas playground chips are hardwood chips that tend to hold onto eachother.

- Paver sand paths also can provide a nice aesthetic. Often used in coastal areas amongst the pines, they fit in nicely on a generally sandy site.

- I like to reuse old flagstones and drop them on the mulch, as shown in the small path into the shade garden in the back.

Edging along pathways can be useful to help keep them defined/tidy. Many options are available to suit individuals’ tastes and budgets.

Side Yards

In many residential neighborhoods, the sides of the property can be shady, so the design incorporates plants that can do well if there is shade along the east side of the house. A mix of taller and shorter grasses and wildflowers generates interest across the seasons, and some shorter shrubs—here including huckleberry—have been included to provide continuity and legibility as the eye tracks back through the landscape. Highlighted plants in this area include:

East Side of House

American beautyberry (Calicarpa americana) is grouped in threes toward the front and the back of the house, which creates a repeating pattern that helps people recognize the intentionality of the design. Beautyberry is a classic shade-tolerant shrub that is frequently found in the Coastal plain and is popular for its clusters of magenta berries that last well into the winter. It produces berries on new growth, and can be pruned as needed in late winter or very early spring (before new growth begins), both to simulate the browsing the shrub would sustain from animals in the wild, and to retain a desirable size and shape. Tips on pruning are given in the maintenance section. The berries are not the tastiest first choice menu item for hungry birds, so they tend to be left for later, but they do offer a helpful food source during the leaner, later months.

Black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), a host plant for the red-spotted purple butterfly (Limenitis arthemis), Henry’s Elfin butterfly (Callophrys henrici), and huckleberry sphinx (Paonias astylus), and also a source of food and shelter for other wildlife. Mature specimens typically reach a height and spread of 1 to 3 feet, a manageable size that makes them good choices to add some layering to a narrow bed.

West Side of House

As on the east side of the house, using some tallish grasses that won’t crowd the relatively narrow space helps provide a nice divider with the adjacent property while providing some habitat. Noting the row of pines in the neighbor’s yard I chose a coastal pine flatwood theme for the area. This simple planting includes a row of lyreleaf sage (Salvia lyrata) in front of a backdrop of wild rye (Elymus virginicus) and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia). A trail of threadleaf coreopsis (Coreopsis verticillata) on the south and gray goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis) to the north visually blend the path from the front yard to the backyard, respectively.

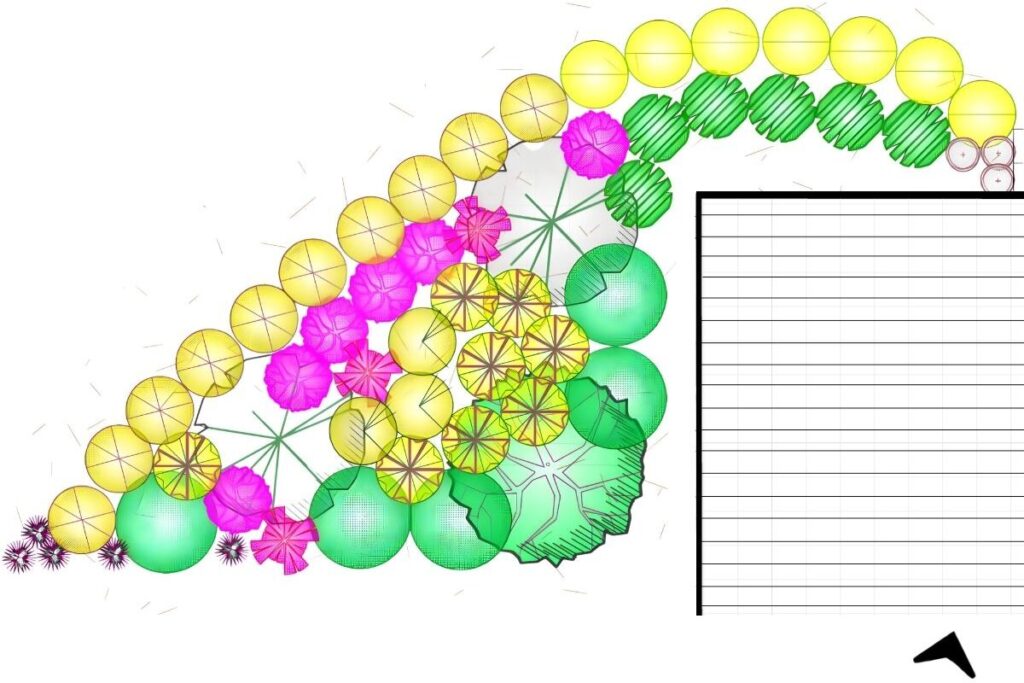

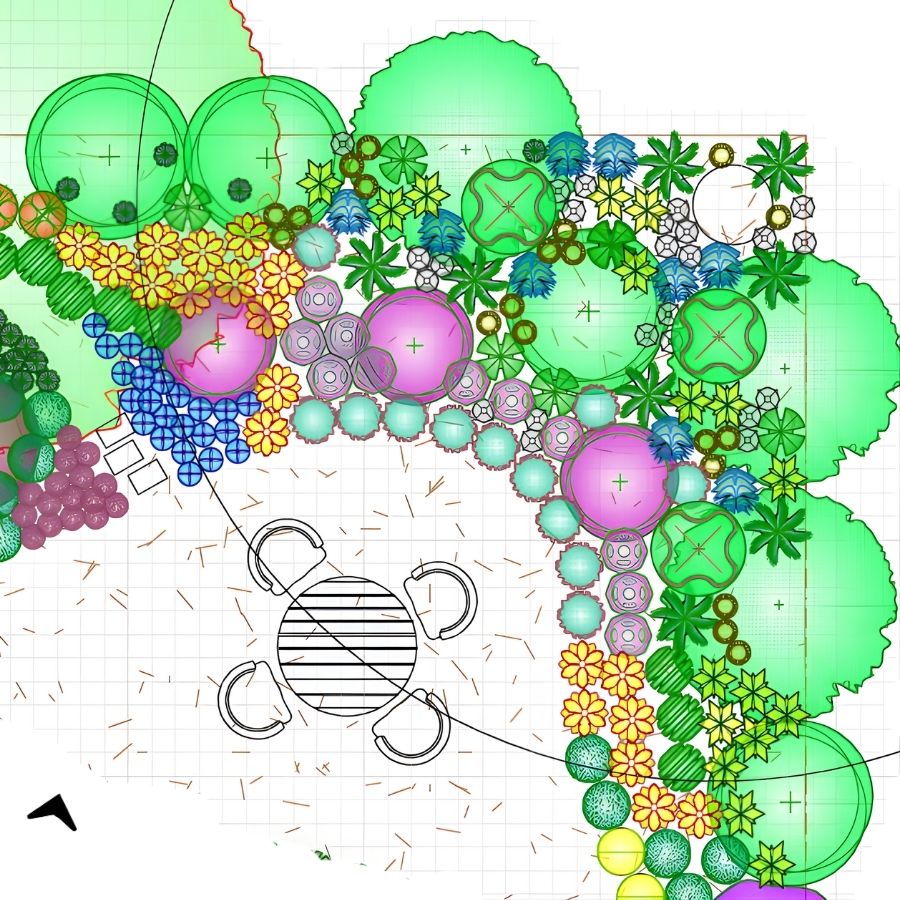

Backyard

Deck Area

The east side of the deck offers another opportunity for a diverse planting. In this design, the bed is anchored by three black chokeberries (Aronia melanocarpa), another common, medium-sized shrub. In the rose family, black chokeberry produces clusters of large, edible berries, the astringent tartness of which gives rise to its common name. It is commonly cultivated in Europe, where selections are grown for fruit used to make jams and jellies. Indeed, chokeberry may likely be an important fruit of the future as it is tolerant of heat, drought and changing weather conditions. Red chokeberry (Aronia arbutifolia) also is available, native in the Richmond area, and could be used in this spot, but red chokeberry may grows a little larger, and black chokeberry may be slightly easier to obtain from commercial sources.

A spot on the immediate west side of the deck is well-drained but remains moist. Here, I included some plants that will benefit from the moisture and sun. Included are:

- Sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana): Evergreen to semi-evergreen in this region, an important understory shrub or small tree in wetlands.

- Common elderberry (Sambucus canadensis): A fast-growing, clonal shrub producing white flowers and purple berries relished by birds; also valued for its medicinal uses.

- Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica): A medium-sized shrub commonly found throughout the region.

- Eastern gamma grass (Tripsacum dactyloides): A large clumping grass native to floodplains.

- Cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata): A tall wetland species producing multiple stalks of yellow blooms.

- Swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata): A key monarch host plant for sunny, moist sites. Group several plants together to help female monarchs locate them for egg-laying. This design includes both A. incarnata and A. tuberosa for seasonal and site diversity.

- Roughstem goldenrod (Solidago rugosa): A late-season wetland goldenrod offering color and nectar for pollinators.

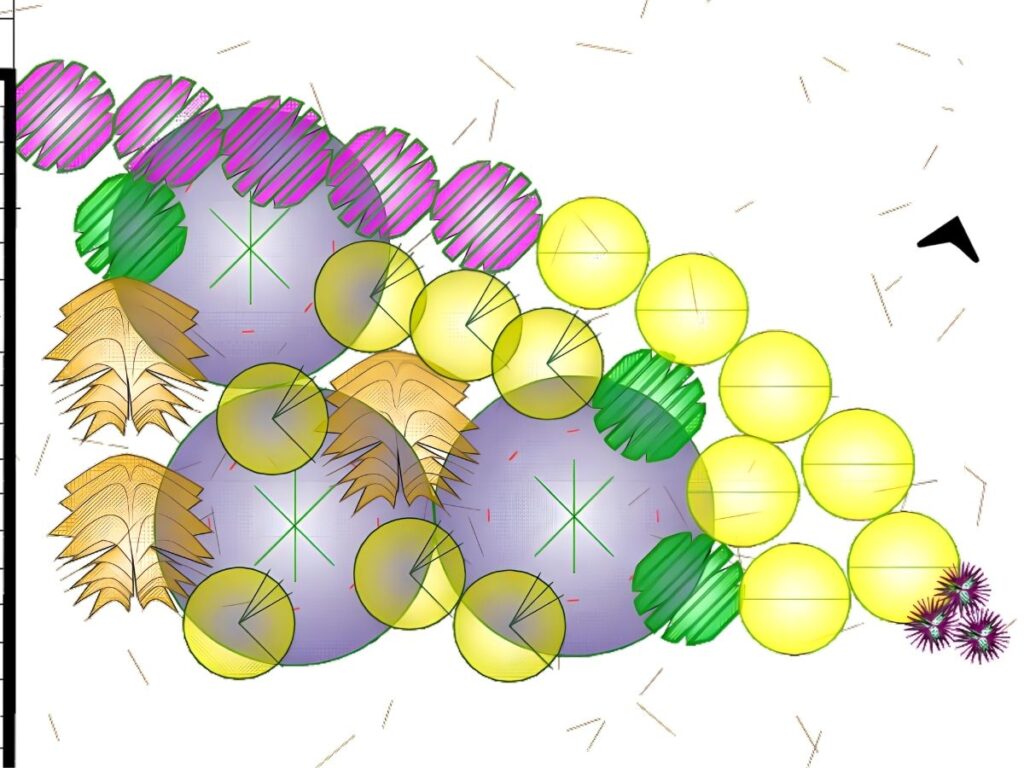

Northwest Corner

Opposite the deck on the west side, the plantings begin to transition toward the area under the new southern red oak (Quercus falcata). Here, plantings include:

- Fleabane (Erigeron philadelphicus): A smaller clonal wildflower found in many conditions but particularly in moist sun.

- Fringed sedge (Carex crinita): A large wetland sedge.

- Wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana): Used as a groundcover with elderberries. It readily spreads, is semi-evergreen, and provides edible fruit.

Planting a new canopy tree like a southern red oak is a legacy contribution to the environment. Keeping the growth of the new oak in mind, this part of the design includes wildflowers and shrubs that have both sun and shade tolerance, which will enable them to handle the changes in the landscape over time. Over several decades, this space will evolve to become quite shady. Highlights of this planting bed include:

- Southern wax myrtle (Morella cerifera): A large evergreen shrub with glossy leaves and a dense growing habit. It will act as a buffer shrub on the property line and is a classic coastal plain species that can grow in nearly any condition.

- Cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis): A great hummingbird plant that thrives in both sun and shade. In shadier conditions, it can tolerate drier soil than it normally would in natural habitats.

An informal woodland path takes advantage of more consistent moisture in this shady area and features some larger wetland wildflower species along with an edge that uses smaller clonal wetland species. Later-blooming perennials offer pollinator support, and the combination of plants provides both useful focal points and some height and a sense of privacy in this area. Included are:

- Sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia): A larger shrub found in the region that thrives in wetland conditions in sun and shade.

- New York ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis).

- Joe-pye weed (Eutrochium fistulosum): A tall and attractive pollinator powerhouse that draws butterflies, skippers, native bees, hummingbirds, and beneficial wasps, and also acts as a host plant for the caterpillars of several native moths.

- Boneset (Eupatorium sessilifolium): Echoing the use of boneset in the front.

- Virginia blue flag iris (Iris virginica): A common wetland species that does well in some shade.

- Blue mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum): A lovely plant and prolific reseeder that will help fill in spots and outcompete weeds.

Northeast Corner

The rear north corner of the property is organized around the shade of an existing large oak. The species selected incorporate some you may find in an acidic oak-hickory community. The plantings also include keystone species like asters and goldenrods that will provide late-season blooms. A few highlighted species include:

- Arrowwood viburnum (Viburnum dentatum): A common large viburnum shrub that thrives in dry shade.

- Paw-paw (Asimina triloba): Continuing the theme of edible natives. Paw-paw has a very large, unique fruit and is well adapted to dense shade as an understory tree.

- Blue wood aster (Symphyotrichum cordifolium): A shade-tolerant, small aster species.

- Blue stem goldenrod (Solidago caesia): A very shade tolerant goldenrod and a common component of shaded oak communities.

- White wood aster (Eurybia divaricata): Another aster that is clonal, spreads readily, and is extremely shade-tolerant. White wood aster is one of those end-of-season blooming asters that will bloom prolifically, even in the densest shade. Colonies of this plant will bring bee species into the dense shaded understory, which is quite a contrast to where we may think about typically seeing them buzzing around full-sun wildflowers.

- Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides): A common fern in many shaded environments.

- Blue wood sedge (Carex flaccosperma) and rosy sedge (Carex rosea): Add texture within the understory layers of the planting. C. rosea offers a very attractive, fine leaf blade, a striking contrast to the C. flaccosperma’s big, blue-green blades.

Maintenance

There is no such thing as a maintenance-free landscape. Our native plantings and naturalistic gardens are still, at their core, managed gardens that will always require some care, but with native plant landscapes the most effort is usually required during the establishment of new plantings.

Watering

Be prepared to water plants through establishment. Smaller plants generally establish faster, but in a new landscape it’s best to be cautious and water all new plants daily through a hot, dry summer. Larger shrubs and trees may take one to two years to establish. As long as the soil drains well, it’s difficult to overwater, so when in doubt, water.

After the first full season and a winter of dormancy, larger trees and shrubs will be less sensitive to drought. Continue to monitor soil moisture and respond as needed. Once established, properly placed natives usually will not need supplemental water or fertilizer, but it is never a bad idea to water a little bit during unusually bad droughts.

Weeding and Mulching

Be prepared to weed for a time as the new plants grow in. There is a very good chance the soil has an extensive seed bank, and the soil disturbance of planting the new plants may cause weeds to germinate.

Applying an initial layer of mulch will cover exposed soil and help suppress a lot of weeds. I usually recommend putting down 2-3 inches of a double-shredded hardwood or wood chip much when the plants are installed. The mulch helps retain moisture and suppresses weeds, and it will eventually break down and contribute nutrients to the soil. You probably won’t need to mulch again, as the natives will spread to fill in the open spaces.

Around deciduous canopy trees, you also can expect a lot of free mulch in the form of leaves, which I recommend leaving as much as possible. Trees need their leaves through the whole yearly cycle, and wildlife species also depend on them. Our woodland plant species have evolved to push through leaf litter, so as long as it’s not very thick or very wet it shouldn’t cause any problems. You can gently move the leaves away from the base of any of more sensitive plants if you desire, especially when the landscape is younger or the plants are smaller and younger, but if you have planted plants that evolved to live under deciduous canopy trees, they will be right at home with the leaves that fall from those trees.

Even after establishment, pioneer species and invasive plants will continue to show up, so developing a consistent maintenance routine will help keep the task from getting overwhelming. As the natives grow and spread and you keep the seed bank suppressed, weeding should slowly get easier. Part of the goal with denser plantings is for the new plants to grow in and outcompete the weeds so even if you start with small plugs, you should notice a significant reduction in weed pressure by the third year.

American Elderberry(Sambucus canadensis)

Anise-Scented Goldenrod(Solidago odora)

Arrowwood Viburnum(Viburnum dentatum)

Beautyberry(Callicarpa americana)

Black Chokeberry(Aronia melanocarpa)

Black Eye Susan(Rudbeckia fulgida)

Blazing star(Liatris spicata)

Blue Mistflower(Conoclinium coelestinum)

Blue Wood Aster(Symphyotrichum cordifolium)

Blue Wood Sedge(Carex flaccosperma)

Bluestem goldenrod(Solidago caesia)

Boneset(Eupatorium perfoliatum)

Butterfly Weed(Asclepias tuberosa)

Calico Aster(Symphyotrichum Lateriflorum)

Cardinal Flower(Lobelia cardinalis)

Christmas Fern(Polystichum acrostichoides)

Cutleaf Coneflower(Rudbeckia laciniata)

Dotted Horsemint(Monarda punctata)

Early goldenrod(Solidago juncea)

Facahatchee grass(Tripsacum dactyloides)

Foxglove Beardtongue(Penstemon digitalis)

Gray goldenrod(Solidago nemoralis)

Huckleberry(Gaylussacia baccata)

Indian Grass(Sorghastrum nutans)

Joe Pye Weed(Eutrochium maculatum)

Lanceleaf Coreopsis(Coreopsis lanceolata)

Little bluestem(Schizachyrium scoparium)

Long-fringed sedge(Carex crinita)

Lyre-leaf sage(Salvia lyrata)

Maple leaved viburnum(Viburnum acerifolium)

Mountain Laurel(Kalmia latifolia)

New England Aster(Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

New Jersey Tea(Ceanothus americanus)

New York Ironweed(Vernonia noveboracensis)

Ninebark(Physocarpus opulifolius)

Ox eye false sunflower(Heliopsis helianthoides)

Pawpaw(Asimina triloba)

Pinxster azalea(Rhododendron periclymenoides)

Purple Love Grass(Eragrostis spectabilis)

Redbud(Cercis canadensis)

Rosey sedge(Carex rosea)

Rough goldenrod(Solidago rugosa)

Shrubby St-John's wort(Hypericum prolificum)

Slender Mountain Mint(Pycnanthemum tenuifolium)

Smooth Blue Aster(Symphyotrichum laeve)

Strawberry(Fragaria virginiana)

Swamp millkweed(Asclepias incarnata)

Sweet Bay Magnolia(Magnolia virginiana)

Sweet Pepperbush(Clethra alnifolia)

Threadleaf Coreopsis(Coreopsis verticillata)

Violet(Viola sororia)

Virginia blue flag iris(Iris virginica)

Virginia Sweetspire(Itea virginica)

Waxmyrtle(Morella cerifera)

White Daisy Fleabane(Erigeron philadelphicus)

White Wood Aster(Eurybia divaricata)

Wild Columbine(Aquilegia canadensis)

Wild Geranium(Geranium maculatum)

Wild Rye(Elymus virginicus)

Woodland Phlox(Phlox divaricata)

Woodland Sunflower(Helianthus divaricatus)

ABOUT THE DESIGNER

Pete Corbino was born in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Virginia. He currently lives in Fairfax County and is the owner of District Native Plants, where he provides native plant consultation, design, and installation services to clients in Virginia and the Washington D.C area. He has also worked with Florida Native Plants and Landscaping in Sarasota, Florida. He is passionate about nature and the outdoors, and he enjoys spending as much time outside as possible. He is an ISA Certified Arborist®, a certified Chesapeake Bay Landscape Professional, and a contractor with the Virginia Conservation Assistance Program (VCAP). Pete’s goal is to help people bring nature back to the land that they steward by planting for wildlife.