Printing note: This design was created to be 8.5″ x 14″ and the design pdf will print best on legal size paper.

Wild Ones Meet the Designers Webinar

Princeton Discussion with Designers Lisa McDonald Hanes & Julie Snell

Designer’s Statement

The Mid-Atlantic Region, Princeton, NJ, specifically, was inhabited before the American Revolutionary War. Land development patterns and housing types show this age coupled with modern demands for density and ways of living that meet a wide range of population needs from university students to young families to the elderly. For this reason, our example housing templates look different than the other cities and regions represented in the Wild Ones native garden designs. The designers recognized that an example of native garden design must offer ideas that can be applied to all the ways we are living in our region today.

The designers encourage those using these two garden templates to understand their place within the ecoregion. The potential complexity of gardening can sometimes feel overwhelming. Even we are sometimes hindered by this. But let’s not be! All gardening is experimentation and a handshake with the natural world where there are no guarantees. Just begin; start trying and learning. Not everything works out, so go easy on yourself.

The pandemic revealed the importance of healthy outdoor spaces close to where and how we live. Our design practice focuses on making positive places for people while building resilient landscapes for today’s climate impacts and ecosystem health. If you only have access to a small outdoor space, you can still be a native plant gardener. If you have access to a large parcel of land, you can contribute to the health and well-being of the larger community. Creating a native plant garden will provide food and habitat for native insects and birds, improve stormwater management, clean the air, and overall provide beauty and joy. The majority of land in the United States is in private hands. Begin doing your part in Wild Ones Honorary Director Doug Tallamy’s Homegrown National Park one step at a time.

Soil

Start with a soil test. The Princeton area spans the transition from the Inner Atlantic Coastal Plain – with soils of gravels, sands, and silts – to the Ridge and Valley ecoregion, where soils tend to be stony, shallow, acidic, and not very fertile. Valley soils are derived from sedimentary stone and glacial till tends to be well-drained, deeper, and fertile. This may be the parent material for your soil, but you may find urban fill or cycles of disturbance in built-up areas.

Climate

Our humid, hot summers are getting warmer and our winters less cold. If you are on a ridge, perhaps you have more air flow than if you are in a valley where humidity or lack of wind may affect your garden with powdery mildew. Our significant annual rainfall is growing, though we experienced drought conditions in the summer of 2022. This was followed by the soaking rains following two hurricanes/tropical storms. Plan around the feast or famine cycles by understanding your place within your watershed. If you are on a ridge, perhaps you have free-draining soils that shed water versus in a valley where water will collect. Consider ways to manage stormwater; you may need to direct it, slow it down, allow it to sink in or store it.

Anthropogenic Influences

The age or density of development in your area may significantly impact the quality of landscape areas. Cycles of disturbance in developed areas often cause the loss of top layers of soil, low organic matter, causing high rates of compaction. Extensive paved areas of roads and parking lots impede stormwater infiltration and increase the velocity and volume of stormwater being directed to the sewer systems. Building materials, concrete, brick, stone, and black asphalt roofs hold heat and increase the urban heat island effect keeping ambient temperature elevated even during nighttime hours. These are all reasons to improve the ecological function of your landscape to lessen the impacts of development.

Understanding the Drawings

Plan and elevation are different types of drawings used by landscape architects to graphically represent a design. A plan drawing is a drawing showing a view from above. A site plan is a common design drawing for graphic representation of a layout, showing relationships between structural and landscape elements to scale. They are not drawn in perspective and there is no foreshortening. An elevation drawing shows a vertical depiction looking straight at a space from a particular line within a site, as if you were directly in front of a building and looked straight at it. Elevation drawings are orthographic projections. Elevations are not drawn in perspective, and there is no foreshortening.

Methodology

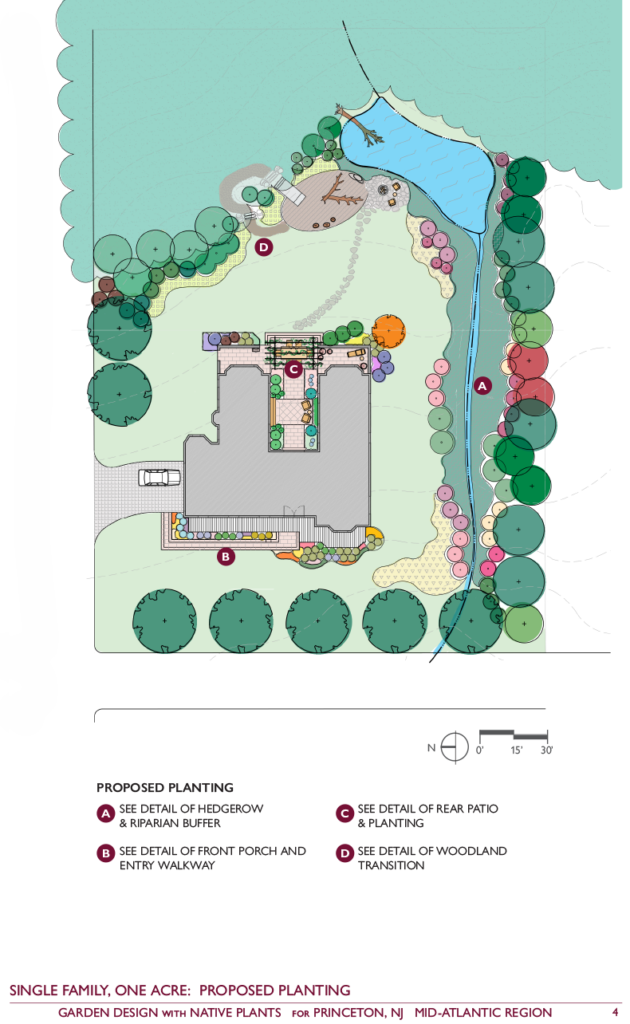

The Single-Family, Large Parcel Template offers ideas for tackling common issues such as fragmented woodland with pressure from invasive plant species, drainage or erosion problems from active water flow and ponding, and damage from overpopulation of deer and rabbits. This large single-family home sits on a sloped one-acre property in the rolling hills of suburban New Jersey. The property has two sides of road frontage. The wooded east side at the top of the slope backs onto a public natural area. This woodland has been heavily decimated by deer browse—where there should be native understory, it is filled with exotic invasive plants. Along the south side of the property runs a small stream. The lawn is mowed to the stream edge with no vegetation to stabilize the bank, making it susceptible to erosion.

To begin the design process, the designers started with a site inventory and analysis. Exposure, aspect, and slope were noted; water flow, erosion, and ponding were observed; the quality and composition of existing plants and stream banks were studied, and evidence of deer pressure documented. The amount of mown lawn was noted, as was erosion along the stream edge and the general lack of outdoor space for the residents to use in a meaningful way. The landscape offered very little biodiversity, seasonal interest, or views to enjoy the natural features of the pond, woodland, and stream.

The design intends to restore ecological function by removing invasive plants, reestablishing native plants suitable to the various landscape types and reinforce slopes with stabilizing plants to dissipate intense water flows and absorb runoff. Planting shrubs and trees on the upland above the pond will help slow the water as it arrives on site. Removing lawn and planting meadows will slow and remove sediment from the water after a heavy rainfall. On this property, understanding native plant communities that thrive in N.J. woodlands and on sunny streambanks will inform the selections and increase the chances of success.

The design intent is also driven by providing more beauty and allowing use options by the human inhabitants. Amenities include arrival gardens and intimate usable outdoor space near the home, larger usable outdoor space and nature-based play within the landscape, hedgerow screening from neighbors that continues the patch woodland and builds a better riparian buffer.

Value is generated by providing diverse amenity spaces and returns the landscape to a healthy plant palette that serves the human inhabitants and the full ecosystem. The design touches on many aspects of landscape design and restoration, intending to demonstrate working with appropriate professional disciplines beyond work homeowners can achieve themselves to realize the design goals. Site hydrology, invasive plant management, and deer pressure were essential considerations at this location that guided decision-making. Plant selection was driven by fitting the right plant to soil and light conditions, resistance to deer damage, and the highest yield in ecosystem function.

Where to begin? On a large property like this with competing interests, it may be best to start with addressing any hazardous conditions first – dead or damaged large trees, flooding and erosion, or invasive species encroachment – then move to stabilization such as replanting in the woodland and streambank stabilization, and lastly proceed to create new amenities and garden spaces. It is good to begin with defining your goals for the landscape and your capacity to help you decide what parts you need help with and which things you can choose to tackle on your own. Search out the needed landscape professionals suited for each phase of the project. The Designers suggest the following priorities. The work within each priority area can be phased in over time and is intended to be accomplished in coordination with various landscape professionals as needed, and as time and money allow.

Priority 1: Woodland Restoration and Invasive Plant Management

Begin by consulting an ISA-certified arborist to identify keystone species, evaluate woodland tree health and recommend any necessary removals and a pruning schedule. Begin invasive plant removal in the woodland with a small area so that replanting can happen as other plants are removed. Any removal actions must be paired with a replanting/restoration action using deer-resistant plants and exclusionary wire fencing. Consider working with a landscape contractor specializing in restoration or land management to control invasive plants and reestablish native understory and groundcover layers. Information on invasive identification and removal practices can be found here: https://www.dcnr.pa.gov/Conservation/WildPlants/InvasivePlants/InvasivePlantFactSheets/Pages/default.aspx

Develop a palette of understory trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants to begin planting in the woodland. Think about locations for access points or trails into the wooded area and views from the surrounding landscape; plant flowering shrubs and trees to demarcate entrances and enhance the edge transition.

Priority 2: Lawn Reduction and Riparian Buffer

Consider how much lawn area you want or need for circulation or play. Consider reducing lawn area to increase biodiversity; this can be phased in over time. Select a manageable area of lawn to remove along the pond edge and replant with stabilizing plants. Larger species will obscure the view of the pond from the house and patio, so consider low-growing herbaceous and ornamental grass deer-resistant plants such as rush and sedge. Rutgers University has research here: https://njaes.rutgers.edu/deer-resistant-plants/

Select a manageable area of lawn to remove along the stream edge to begin streambank restoration. Consider live staking, a low-cost method that reintroduces vegetation directly into the riparian buffer. Stem cuttings taken from trees or shrubs during their dormant season are directly inserted into degraded stream banks. These cuttings effectively anchor themselves on the edges and prevent further erosion. Several plant species are often deployed as bank stabilizing, quick growing plants. See link to Penn

State extension for guide to utilizing live-staking: https://extension.psu.edu/live-staking-for-stream-restoration Several species that root well from cuttings are Cornus sp. (dogwood), Salix sp. (native willows), Sambucus canadensis (elderberry), Cephalanthus occidentalis (Buttonbush). Continue streambank restoration alternating areas of higher vegetation with lower and create access points to the stream with stepping stones. Plants effective for stabilizing a streambank can be found here:

Continue reducing lawn along the stream and begin to reduce lawn in the front yard using solarization techniques and other methods appropriate for slopes. Summer is a good time to begin solarization to prepare for fall planting, allowing time for seed germination or root growth before plant dormancy and the ground freezing.

Priority 3: Canopy & Pond Edge, House Arrival and Patio Gardens

Plant canopy trees along the road on the west side of property. Begin to build a sitting and play space with garden around the pond. To eliminate lawn to prepare for gardens, consider a strategy called solarization.

Resources

Invasive Species

Invasive Plants

- Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health

- Mid-Atlantic Exotic Pest Plant Council Plant List

- P.A. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

Research

PLANT LIST

The list includes plants for a sun to woodland garden, with natural water flow and ponding, and browsing pressure from deer and rabbits. Plants with play value for people are included.

American Hazelnut(Corylus americana)

American Holly(Ilex opaca)

Arrowwood Viburnum(Viburnum dentatum)

Bicknell's Sedge(Carex bicknellii)

Black Elderberry(Sambucus canadensis)

Black Gum(Nyssa sylvatica)

Blue Flag Iris(Iris versicolor)

Blue Wild Indigo(Baptisia australis)

Blue-eyed Grass(Sisyrinchium L.)

Bluestar Flower(Amsonia tabernaemontana)

Blunt Mountain Mint(Pycnanthemum muticum)

Bottlebrush Buckeye(Aesculus parviflora)

Bush Honeysuckle(Diervilla lonicera)

Butterfly Weed(Asclepias tuberosa)

Buttonbush(Cephalanthus occidentalis)

Coastal Doghobble(Leucothoe axillaris)

Coastal Witch Alder(Fothergilla gardenii)

Crested Iris(Iris cristata)

Culver's Root(Veronicastrum virginicum)

Curly Wood Sedge(Carex rosea)

Cutleaf Coneflower(Rudbeckia laciniata)

Dense Blazing Star(Liatris spicata)

Dwarf Bush Honeysuckle(Diervilla lonicera)

Field Pussytoes(Antennaria neglecta)

Flowering Dogwood(Cornus florida)

Foam Flower(Tiarella cordifolia)

Fox Sedge(Carex vulpinoidea)

Foxglove Beardtongue(Penstemon digitalis)

Fringetree(Chionanthus virginicus)

Golden Ragwort(Packera aurea)

Hairy Alumroot(Heuchera villosa)

Hairy Wood Mint(Blephilia hirsuta)

Highbush Blueberry(Vaccinium corymbosum)

Hubricht's Bluestar(Amsonia hubrichtii)

Ironweed(vernonia lettermannii)

Kalm's St. John's Wort(Hypericum kalmianum)

Lanceleaf Coreopsis(Coreopsis lanceolata)

Little Bluestem Grass(Schizachyrium scoparium)

Lurid Sedge(Carex lurida)

Marsh Marigold(Caltha palustris)

Meadowsweet(Spiraea alba)

New England Aster(Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

New Jersey Tea(Ceanothus americanus)

New York Ironweed(Vernonia noveboracensis)

Obedient Plant(Physostegia virginiana)

Ostrich Fern(Matteuccia struthiopteris)

Pale Purple Coneflower(Echinacea pallida)

Prairie Dropseed(Sporobolus heterolepis)

Queen of the Prairie(Filipendula rubra)

Red Chokeberry(Aronia arbutifolia)

Red Osier Dogwood(Cornus sericea)

Slender Mountain Mint(Pycnanthemum tenuifolium)

Soft Rush(Juncus effus)

Spotted Joe Pye Weed(Eutrochium maculatum)

Steeplebush(Spiraea tomentosa)

Swamp Milkweed(Asclepias incarnata)

Swamp Rose-mallow(Hibiscus grandiflorus)

Swamp White Oak(Quercus bicolor)

Sweet Fern(Comptonia peregrina)

Sweet Gum(Liquidambar styraciflua)

Switchgrass(Panicum virgatum)

Tall Coreopsis(Coreopsis tripteris)

Virginia Rose(Rosa virginiana)

Virginia Sweetspire(Itea virginica)

White Turtlehead(Chelone glabra)

Whorled Milkweed(Asclepias verticillata)

Wild Bergamot(Monarda fistulosa)

Winterberry(Ilex verticillata)

About the Designers

Lisa McDonald Hanes is a registered Landscape Architect, co-owner/operator of Redbud Native Plant Nursery and a founding principal of TEND landscape architects. With a land ethic formed from her family’s farming heritage and more than twenty years of professional work with landscapes, Lisa’s focus is fostering connections between people and their environments and improving quality of life by altering how we perceive, use and care for landscapes. Educated at Purdue University, with a Bachelor’s of Science in Landscape Architecture, Lisa has worked directly with community groups, municipal agencies, a wide range of design professionals and private homeowners in cultivating landscapes like our health depends on it.

Julie Snell is a founding partner of TEND landscape architects and co-owner/operator of Redbud Native Plant Nursery in Media, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia. Julie has a background in Fine Arts, a Master’s Degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania and is a certified arborist. For more than twenty years, Julie has worked in both the public and private realms, focusing on the bridge between design and landscape management. As founder and co-chair of the Landscape Management Forum, she has forged a partnership with landscape managers throughout the Philadelphia region. Julie has been an adjunct instructor at Temple University in the Department of Landscape Architecture and Horticulture. She is currently serving on the Board of Trustees for the Ecological Landscape Alliance.

Free National Webinar: Rethinking Horticulture with Real Ecology presented by Joey Santore

March 18th at 6:00 PM (CT)

Join Joey Santore, creator of Crime Pays But Botany Doesn’t, for a candid Wild Ones National Webinar examining how inherited garden aesthetics shape native plant landscapes. Drawing on field experience and real ecology, Joey challenges tidy design norms and explores why dense, irregular plant communities are often the most resilient and ecologically sound.

About Wild Ones

Wild Ones (a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization) is a knowledgeable, hands-on, and supportive community focused on native plants and the ecosystem that depends on them. We provide resources and online learning opportunities with respected experts like Wild Ones Honorary Directors Doug Tallamy, Neil Diboll, and Larry Weaner, publishing an award-winning journal, and awarding Lorrie Otto Seeds for Education Program grants to engage youth in caring for native gardens.

Wild Ones depends on membership dues, donations and gifts from individuals like you to carry out our mission of connecting people and native plants for a healthy planet.

Looking for more native gardening inspiration? Take a peek at what our members are growing!